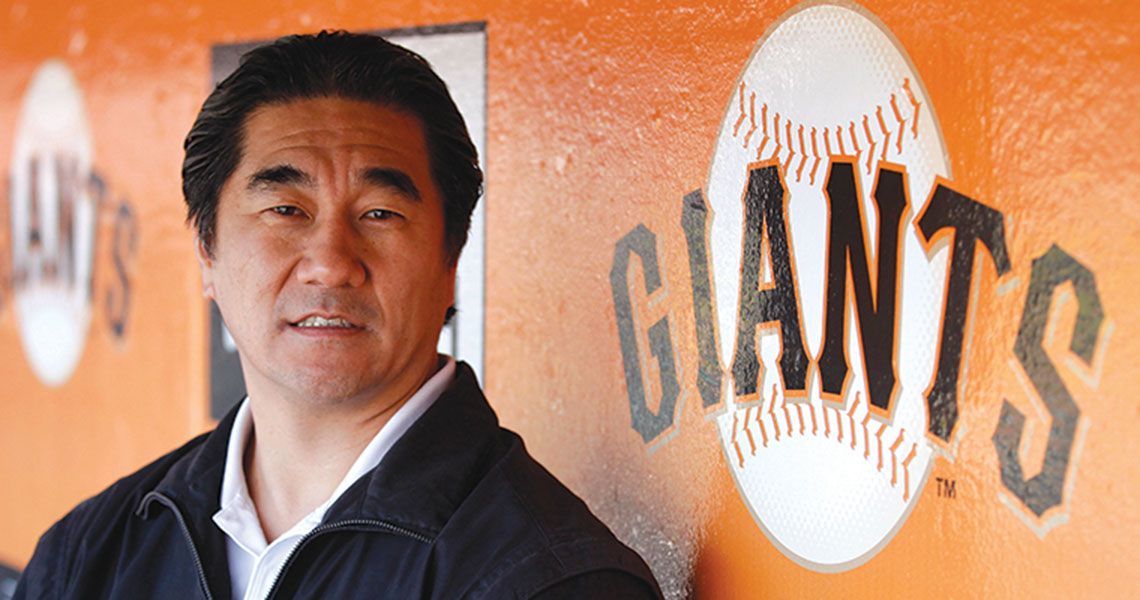

As he anticipated the final out in the World Series last November, Ken Akizuki, M.D. ’93, ran from the San Francisco Giants’ clubhouse to the end of a tunnel behind the team’s dugout. When the Giants won, the team’s orthopedic surgeon followed the hugging, screaming, jumping players onto the field to celebrate.

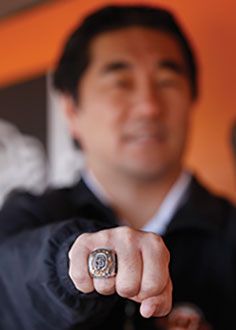

The next day, Akizuki rode in the team’s victory parade through downtown San Francisco. A sea of confetti coated a roaring sidewalk crowd estimated at more than 1 million. Later, the Giants awarded Akizuki the same World Series ring the players and coaches received.

“I wear the ring every day,” Akizuki says. “And every day my patients want to wear it and take a picture with it. I think my patients are more interested in my ring than they are in me.”

Celebrating the World Series championship with the team and owning a World Series ring are just two among many fantasy “perks” Akizuki receives as the Giants’ orthopedic surgeon.

He doesn’t have to search to uncover the path that led him to this moment. For Akizuki, it began during his final year as a student in the George Washington University’s School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS), as he prepared to pick a residency.

“It was tough to choose a specialty, because as a student you wanted to emulate the professors you liked and looked up to,” recalls Akizuki. “But the seed to go into orthopedics was probably implanted in my fourth year of medical school. My GW professors helped me get a great residency in general surgery at Los Angeles County Harbor–UCLA Medical Center, and when I went into the residency I felt that my education was as good as what was provided by any medical school in the country.”

He adds, “I can’t tell you how many other professors and people touched my life. My classmates and faculty were tremendous. The impact of the mentors and other people I met was invaluable. I was helped a great deal by a couple of orthopedic residents: Ken Yamaguchi, now the Sam and Marilyn Fox Distinguished Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and Ammar Bafi, who was the chief resident in general surgery and is now a cardiovascular surgeon at Washington Hospital Center.”

In his role with the Giants, Akizuki works at nearly all of the team’s 81 yearly home games and spends another three weeks with the Giants during spring training. That’s in addition to his full-time practice in San Francisco.

Akizuki works the games not just because he’s been a Giants fan since childhood, and not just because in the clubhouse he regularly encounters Major League Baseball royalty, such as former Giant Willie Mays or such current players as two-time Cy Young Award winner Tim Lincecum. He’s at the clubhouse because he feels responsible to the players.

“Baseball’s a funny game,” says Akizuki, 45. “The majority of injuries are a result of repetitive stress, and the more you are around, the more you get to see the evolution of injury and you get to know the athlete and they get to see you. The more you’re around and the better the players know you, the more they trust you.”

Akizuki starts each season with the Giants in late February at spring training in Scottsdale, Ariz. He and other team doctors provide physicals for the Giants 180 to 200 major and minor league players and treat frequent pre-season injuries.

When the season starts around April 1, he frequently works 15-hour days. On nights when the Giants play at home, he sees private patients from 7:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. and plants himself in the Giants’ locker room from 6 p.m. to 11 p.m.

When he arrives at the locker room, “There’s usually a list of players I need to see, and I prioritize those,” he says. “Some may be playing that night. I’ll usually meet with the player and training staff and make decisions. A lot of times the player will have taken batting and infield practice, and we’ll assess after that how they’re doing. It’s a long season and a grind. The players are always banged up a little, some more than others, and you’ve got to make decisions on a day-to-day basis.

“I try to multitask, doing paperwork from my practice during the game,” Akizuki continues. “I’m pretty intent on watching the game on a monitor in the clubhouse. A lot of players that are preparing to play in the later innings leave the dugout and come into the clubhouse. They have their rituals to get ready, like relief pitchers who come in and get stretched out. Guys who’ve been injured for a long time come in to rehab, and I talk to them. We watch the game together.”

He adds, “The hardest thing about the job is that the training staff and I have to make a lot of tough decision in terms of injuries. People always want to know how soon and how fast can we get these guys back on the field, and our job is to do so safely and do it right.”

Among those Akizuki has successfully treated were two players struck in the head at separate times by a batted ball. One player was a pitcher on the mound and the other an infielder in the dugout. But common complaints, especially among pitchers, include labral tears, impingements, and tendinitis in the shoulder, and ulna collateral ligament problems in the elbow.

Unfortunately, he says, the injuries, once confined to professionals, are becoming more common among amateur athletes.

“The most concerning thing I see,” he says, “especially in youth baseball, is that kids are getting the same injuries in the shoulders and elbows at a much younger age. At 37, a guy has had a major league career. But at age 12, the concern is that if you’re getting an operation on your shoulder or elbow, how long will the player last? Will they last through high school or college or even professional baseball if that’s their goal?”

As a pitcher–infielder at Branham High School in San Jose, Akizuki personally avoided these kinds of injuries. Although he attended few games as a spectator at that time, because of his own playing schedule, he grew to become an avid Giants fan after his father took him to games at windblown Candlestick Park, the Giants’ former stadium.

“I was always a big baseball fan,” he says. ”I was a sports junkie and watched about every Giants game on TV. You probably always loved Willie Mays, but at that time you wanted to hit like Will Clark.”

After high school, Akizuki graduated from the University of California at Berkeley before enrolling at SMHS. He’s grateful that the medical school stressed the importance of treating not only the injury, but also the whole person. “You are taught the physiology and the anatomy,” he says, “but you’re also taught to always remember that you’re dealing with a human being.”

After applying what he learned during a residency at Los Angeles County Harbor–UCLA Medical Center, he was immediately invited in 2000 to join the Giants medical team. He became the team’s orthopedic surgeon in 2004.

As he’s working in the locker room, he frequently sees Willie Mays and other noted former Giants, such as Willie McCovey and Orlando Cepeda, but it’s the current staff who receive the bulk of his attentions.

“I know all the current players, some of them very well, especially the guys who have been around the Giants a long time. I’ve known Tim Lincecum since we drafted him. We have a nice relationship. Obviously, their relationship with me has a lot to do with the personalities. Some guys just don’t want to see a doctor,” says Akizuki.

“I try not to get involved in players’ lives. They have enough on their hands. I need to be their doctor and maintain objectivity and distance. I love going to work in this environment. Inside me, it’s like a dream. This is the team you rooted for as a kid. You thank your stars every day. You pinch yourself. I want to be a fan and root for them. But you can’t act like a fan. You’ve got to be professional.”