It should have been a routine sonogram. Health officials in rural Thailand, who had been tracking the presence of a parasitic worm in the local population, were checking a 50-year-old woman’s gall bladder for inflammation — a clear indication of the presence of the parasite — nothing more. Normally the gall bladder is a small organ, less than two inches by three inches. But that morning, something else filled the sonographer’s screen: a malignant tumor twice the size of the organ itself.

The shocking size and rapid growth of the tumor — until then, the woman had shown no symptoms — stood out in the minds of everyone involved. It also perfectly captured the nature of this cancer ravaging Southeast Asia: It’s slow to wake but mean when it does, taking people unawares. Some six million people in Thailand are infected with the cancer-causing worm. An additional 600 million throughout the region are at risk, and up to five percent of those infected develop tumors. What’s more, the cancer preys not only on the body but also on one of the most traditional aspects of Thai life: fish, a staple of the rural diet. It’s like telling Americans that burgers and fries cause untreatable cancer.

Paul Brindley, Ph.D., a tropical disease specialist and professor at The George Washington University Medical Center, dedicates much of his research to unraveling the dangers of the tiny flatworm at the center of all the destruction, Opisthorchis viverrini, or liver fluke. As part of a five-year, $2.75-million International Collaborations in Infectious Disease Research grant with Khon Kaen University, Thailand, he makes three to four trips per year to remote rural areas of northeast Thailand, near Laos. It’s a marshy area, saturated with creeks and pools, and it’s poor, with limited public hygiene. It also has the highest rate of bile-duct cancer in the world, a statistic that Brindley hopes to change.

The epidemiology of the liver fluke infection is clear. Fluke eggs float in marshland water, where snails feed on them. The flukes mature inside the snails, pass through their systems, and emerge as adults in the water. There, they seek out local fish like grass carp and burrow beneath their scales, forming cysts. Both the fish and snail are minuscule. The snail is “half the size of your little fingernail,” Brindley says, while the fish are smaller than a human hand. The flukes are correspondingly tiny, too, and the cysts on the fish are microscopic, invisible to human eyes.

That’s a problem because those fish form an integral part of the region’s diet. Cooking the fish easily kills the liver flukes, but Thai people have eaten the fish raw for hundreds of years. After trapping fish in bamboo baskets or nets, locals ferment and eat them with a sauce in a dish called pla-ra or mince them and mix in chili and Thai condiments as koi-pla (which translates to “raw fish”). Sutas Suttiprapa, a graduate student in Brindley’s lab, ate such dishes when growing up in Thailand, until a school-education program (long since neglected) warned him of the risks. He says both dishes are delicious — spicy and sour at once. But that’s only part of the reason he fears that persuading people to give up eating raw fish will prove difficult: “[People] don’t stop eating it because of the traditional aspect.” He adds, “When they have a festival and invite guests from another community, they’re going to welcome the guests with dishes of raw fish.”

What’s more, combating myths about the fish is hard. “People believe that fermenting will kill the parasite. But they only ferment it two or three days. It would take six months to kill it,” says Suttiprapa. Some also believe that drinking vodka with the dish destroys the worm. Others, he says, “believe if they eat the raw fish, it will make them stronger and healthier. It’s also a ‘guy thing’ — you’re going to be embarrassed if you cook it.”

Once ingested, the flukes worm their way from the small intestine to the liver, where they feed on the cells that line the bile duct. For most people — 70 percent of the population in some areas harbors the fluke — the infection is harmless. The worm grows to a half inch long, lays eggs that are passed through the feces into the watershed, and the cycle starts again. For a fraction of the population, however, the infection in the bile ducts morphs into an aggressive cancer.

One clue about susceptibility to the cancer lies in the treatment of the disease. The drug praziquantel seems to kill the fluke with few side effects. For some, however, “the liver damage — caused by the worm infection — does not resolve after the worm infection has been cleared,” explains Brindley. In fact, inflammation can last for decades, and “if the inflammation doesn’t resolve, they will get cancer.” Pinning down that link between inflammation and cancer has been the goal of Brindley’s study, which wraps up in 2012. In the meantime, his team will continue to screen people and determine the prevalence of the disease.

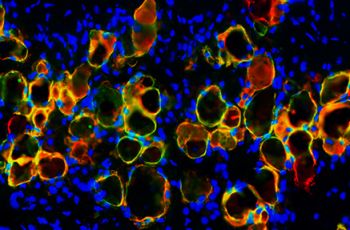

Brindley is also hunting for the molecular cause of the cancer. He notes that approximately one-fifth of all cancers are caused by infections, usually microbial. Examples include forms of cervical cancer (through HPV) and liver cancer (through hepatitis). The body’s immune system responds to infections by secreting substances that kill infected cells, but those substances can also damage the DNA of bystander cells, which go on to develop cancer. That collateral damage might be what is happening with the liver fluke, too. But the fluke does something more than microbes do. Brindley’s other major discovery was that the worm secretes chemicals that cause cells to divide more quickly than normal. That secretion suppresses the “programmed cellular death” that checks such uncontrolled growth. Both are classic signs of cancer.

No one expected a parasite to cause cancer, and the work is helping to open up an entire field of biological carcinogens, which had been limited to microbes. The International Association of Cancer Registries has recently become very interested in identifying how one living creature can give another creature deadly cancer. “And this little worm,” Brindley says, “is at the absolute top of the list.”

Stopping the worm itself is also at top of the list for the people of rural Thailand, including Suttiprapa. Like many, he has personal reasons for fighting to eradicate the cancer: Just last year, he lost his uncle to gall bladder carcinoma. In the future, Brindley’s research — determining who is vulnerable and perhaps even developing tests for early cancer detection — could help save lives. In the meantime, Suttiprapa is putting his hope in another key part of Brindley’s work — the very strategy that saved him from eating too much koi-pla and pla-ra as a youth — education. “We have to ask teachers to teach students . . . to educate younger people,” he says. “It’s very hard to change people’s habits after 20 years.” Not to mention a way of life hundreds of years old.