Imagine a screen flashing calming words, one at a time in succession. To win, all you have to do is read the words. This is the concept for a video game, geared toward young people who suffer with anxiety, thought up by a group of students at T.C. Williams High School. There are no time restrictions in the game, no fast pace; all you have to do is read the serene words.

This is just one of the games that Qing Zeng, Ph.D., director of the Biomedical Informatics Center, and professor of clinical research and leadership at the George Washington University (GW) School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS), helped develop with students. She has been working with a biotech class at the Alexandria, Virginia, high school. Zeng worked with Linda Zanin, a community outreach specialist at SMHS, to connect with Jennifer Ushe, a STEM teacher at T.C. Williams who wanted to challenge the 11th and 12th grade students in her biotech class.

Zeng began this project before arriving at GW, about a year ago. The first game that she developed, Doodle Health, was a Pictionary-like activity with pictures illustrating discharge instructions to help patients better understand and adhere to those instructions. When she made the move to GW, Zeng brought the project with her.

The research team then brought Doodle Health to the biotech class at T.C. Williams and had them provide feedback. While the project proposal had the team focusing mostly on disparities in health, the students’ curriculum was more focused on genetics, so the students decided to marry the two. “They came up with topics ranging from healthy eating to cancer,” said Jessica Laubach, study coordinator at the Biomedical Informatics Center, who worked closely with Zeng on this project.

The reasoning behind using video games as a format to discuss health is simple, according to Zeng: “I don’t know a child who does not play video games. They are a medium that the kids interact with the most.”

“We of course wanted this to be an educational experience for the students. They did a great job of performing background research and were able to justify why they wanted to focus on those topics,” she added. Zeng described the work of one group that wanted to focus its game towards children with cystic fibrosis. The students cited a paper that found that children at camps for cystic fibrosis actually should not be kept together, as they risked a cross-contamination of sorts. These students wanted to develop a social networking channel that would keep those children engaged as they were kept from others like themselves.

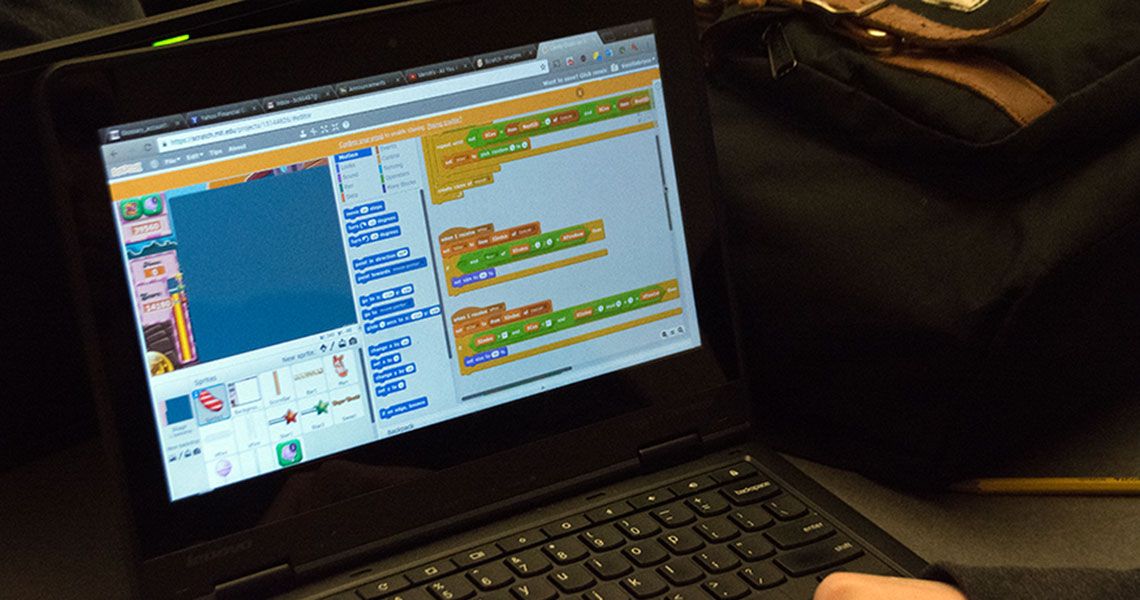

The students used a “design box” brainstorming method to generate game ideas — encouraging students to consider what the content of their game should feature, who the intended audience should be, the mechanics behind the game, and the technology it would be played on. These games are still very much in the prototype stage, Zeng explained, but they are off to a good start considering the amount of programming skill the students had to learn throughout the project.

Recently, some of the students from the biotech class took a field trip to GW to present the status of their games to the Biomedical Informatics Center and to take a tour of the GW Cancer Center. While none of the games have been published and are still in the prototype stage, a few of the students will return to GW this summer as interns with the Biomedical Informatics Center to work together to see a game to completion. Zeng and Laubach are already in talks with Ushe to develop a plan for the next school year.