At the conclusion of the fall 2014 semester, members of the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS) Class of 2018 embarked upon an intensive three-day clinical public health workshop to develop proposals to achieve an AIDS-free generation. The task: create an innovative, community-based plan to improve one component of the HIV Care Continuum; a model used by federal, state, and local agencies to identify issues and opportunities related to improving the delivery of services to people infected with HIV. On the final day of the clinical public health experience titled “How Physicians Can Help Create an AIDS-Free Generation,” each student working group presented a proposal for discussion and critique during a White House event featuring a panel of top government and public health HIV/AIDS leaders.

A key facet of the revised SMHS M.D. program curriculum, the clinical public health course was designed to introduce medical students to the HIV care continuum and their role as practicing physicians to help end the HIV/AIDS epidemic. The goal was not just to identify what needs to be done to improve the HIV Care Continuum, but to also identify how to do it at the community level.

“Dramatic progress has been made in the last generation to turn HIV infection from a uniformly fatal disease to a chronic, treatable condition. However, obstacles remain at the community level, and that impedes decreasing new HIV infections,” said Lawrence “Bopper” Deyton, M.D. ’85, M.S.P.H., senior associate dean for clinical public health and professor of medicine at SMHS. He explained that the HIV care continuum is a sequence of actions used by clinicians, public health and policy leaders to reduce community obstacles to perpetuating a preventable cycle of HIV infection. A successful continuum will ultimately lead to an AIDS-free generation. The goal of the three-day exercise, Deyton added, “was for the students to propose how to correct a problem, not just define a problem.”

To jump-start the student’s research efforts, local and national HIV/AIDS experts including Anthony Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, addressed the current HIV landscape and the latest scientific advances, treatment, and prevention programs.

“Since the start of the AIDS epidemic more than 78 million people have been infected with HIV, almost 40 million deaths, 35 million people living with HIV, and it’s still ongoing and it’s out of control in many respects,” said Fauci, kicking off the course with his talk, “Ending the HIV Epidemic: From Scientific Advances to Public Health Implementation.”

Over the next day and a half, student received access to community experts as well as the opportunity to visit DC’s Whitman-Walker clinic to meet with staff and patients to gain front line perspectives about barriers to implement the Continuum. The groups conducted their own research, field visits and brainstorming to develop medical science-based innovative, community-based proposals to improve specific components of the HIV care continuum.

For first-year SMHS medical student Michael Kahn, having this opportunity and access to policymakers is unique to being in Washington, D.C. “I think it’s one of the draws of this medical school; It’s one of the reasons I chose to come here,” he said.

As an active clinician, immunologist, and researcher, Fauci knew early on in his career that to make a broader impact, he would have to embrace and interact with those who make policy. Fauci worked side-by-side with every president since Ronald Reagan, and was instrumental in the development and implementation of significant legislation in the fight against HIV/AIDS such as the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR).

Fauci warned that although “we have accomplished a lot and have a lot to be proud of as a nation, as scientists, as clinicians; there is still work to be done.” In the United States, he said, detailing the gravity of the on-going epidemic, “there are 1.2 million people living with HIV, of whom 14 to 16 percent are unaware of their infection.” He encouraged the future physicians to take an active role in policy work and focus on “hot spots” or specific communities rather than thinking about “one-size fits all” prevention plans.

“The end of the HIV/AIDS pandemic is a feasible goal; however there is still much to do,” Fauci said. “Now is not the time for a victory lap but the time for racing ahead. This is particularly relevant for you in this class, because it’s going to be up to you to bring this over the goal line. It’s not going to happen spontaneously.”

Maggie Czarnogorski, M.D., RESD ’06, FEL ’08, M.P.H. ’14, senior policy advisor at the Office of National AIDS Policy at the White House, also took the stage to discuss the HIV Care Continuum. “When we talk about the care continuum this is what we are talking about; it’s framework for looking at people from the time they are infected through their course of treatment to that ultimate health outcome, which is viral load suppression.”

Czarnogorski tasked the medical students to think critically about the challenges, identify successful programs that can be scaled up, and determine what else can be done be to improve outcomes along the HIV Care Continuum.

Ron Valdiserri, M.D., M.P.H., deputy assistant secretary for health for infectious diseases and director of the Office of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Disease Policy at the in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, rounded out the discussion, describing the evolution of HIV/AIDS testing, treatment and prevention programs.

On day-two of the program, students were aksed to define challenges, identify successful best practices, facilitate discussion, and propose areas for immediate research as they pertain to the HIV Care Continuum. They canvased the city to speak with community leaders and experts in the field to help their research efforts.

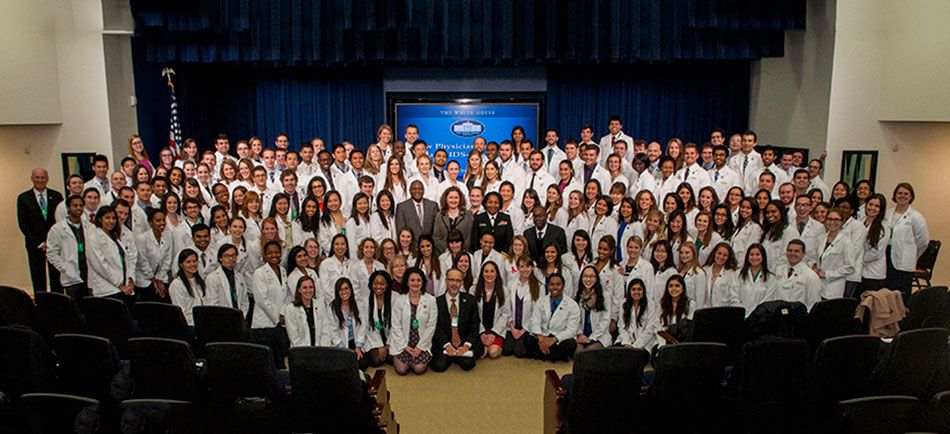

The program culminated at the White House with a presentation of public health recommendations by each group before a panel of HIV/AIDS experts, including: Czarnogorski; Douglas M. Brooks, director of the White House Office of National AIDS Policy; Laura Cheever, M.D., associated administrator for HIV/AIDS at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA); Deborah Parham-Hopson, Ph.D., assistant surgeon general and senior advisor for HIV at HRSA; and Greg Miller, M.P.H., vice president and director for public policy at the American Foundation for AIDS Research. The students offered their policy recommendations on HIV/AIDS testing, screening, prevention, and access to antiviral drugs in the District of Columbia.

“We need your help as future leaders of health care to understand the challenges along the HIV Care Continuum,” said Douglas Brooks, director of the Office of National AIDS Policy at the White House and moderator for the event. “We want to help you understand that your role as physicians can help us end the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States."

For Eli Fredman, first-year SMHS medical student, addressing such an esteemed collection of experts was beyond exciting. “I think that we have come up with some unique ideas and tools that can actually make a difference along the HIV Care Continuum,” he said.

“The tools are out there; it’s just about getting the correct information out there and making everyone aware that these tools exists,” echoed Haydee Del Calvo, first-year SMHS medical student reflecting what she learned over the course of this exercise. “The face of HIV has changed and it’s no longer a death sentence. It’s not something we can manage and treat.”

“As a dean of a medical school who sees himself, along with Dr. Deyton, as an HIV/AIDS activist and physician-activist from the ’80s; to sit here and see you guys investing your time, energy, creativity, and brilliance in helping us come to an AIDS-free generation is really overwhelming” said Jeffrey S. Akman, M.D.’81, RESD ’85, Walter A. Bloedorn Professor of Administrative Medicine, vice president for health affairs, and dean of SMHS.

“GW students will graduate as excellent clinicians. They will practice in a health care system is that is changing dramatically. With a focus on patients as well as the health of populations, we must prepare them” said Deyton. “In order to be successful clinicians and leaders in that changing environment, GW students must expand their scope of practice to include clinical public health. They must know how to use the principles and practices of public health and population health. And we must teach them how to do that.”

For Kahn, the biggest lesson learned is the fact that “as physicians, there are outlets for us to enact change,” he said. “Getting the chance to see a microcosm of the process, from having an idea, to brainstorming with your peers, to having the opportunity to present your plan to the people who can make change gives us the idea that maybe someday down the line we can do this on a much larger scale.”